The Importance of Monomaterial Polypropylene Laminates in Flexible Packaging

- Published: June 27, 2022

By Steve Langstaff, Business Development Manager Packaging & Sustainability, Innovia Films

Last year’s COP26 summit reminded us of the importance of reducing the human effects on the environment with specific emphasis on the need to reduce our carbon footprint. It is well recognized that food production is a major contributor to global warming and resource-efficient packaging plays a vital role in reducing the carbon impact by reducing waste and extending shelf life.

Last year’s COP26 summit reminded us of the importance of reducing the human effects on the environment with specific emphasis on the need to reduce our carbon footprint. It is well recognized that food production is a major contributor to global warming and resource-efficient packaging plays a vital role in reducing the carbon impact by reducing waste and extending shelf life.

Although the carbon footprint of the packaging is important, it is usually comparatively small when compared to the product it is wrapping. This is one of the big advantages of flexible packaging, which due to its light weight, is far more resource efficient than cans, bottles, tubs or trays. However, in most countries flexible packaging is not collected and the infrastructure to recycle is restricted. This can result in non-optimal end of life such as landfill, incineration or waste to energy.

The misconception that flexible packaging cannot be recycled is leading some to poor environmental choices, often leading to increases in food waste and packaging with higher Global Warming Potential than flexible alternatives. Fortunately, things are changing.

There are regular announcements in the press regarding flexible packaging recycling investments and private initiatives to collect flexible packaging (for example, UK supermarkets). As governments start to mandate curbside collections of flexible packaging this will accelerate the industry further.

Examination of the front-of-store collection of post-consumer flexible packaging in the UK, shows that around 70 percent of the material is either Polyethylene (PE) or Polypropylene (PP) and that 20 percent is mixed plastic and aluminium foil plastic laminates. Currently the PE fraction is down-cycled to low-grade PE film for use as garbage bags or supermarket carrier bags. The PP fraction tends to go into rigid uses, much of it outside the packaging industry. The laminate fraction in most situations goes, at best, to waste for energy.

However, technology is available to sort, wash and de-ink the PE and PP fractions to allow them to be “closed loop” recycled; i.e., so they can be used back into high-grade film applications.

Currently no large-scale efficient technology exists to recycle the mixed plastic laminates. So, the current approach is to try and remove them and replace with all PE or all PP structures which form most of the existing waste stream. Mixed polyolefin waste (PE and PP) has a market value, but if the objective is closed loop recycling back into high-grade film, individual streams would be advantageous for film production.

For many primary packaging applications, the high stiffness and transparency of PP has advantages over PE, as PP offers the option to go thinner and to run more efficiently on packaging machines.

Both of which results in a lower carbon footprint.

Both of which results in a lower carbon footprint.

Most laminates in the food packaging industry are formed using the best properties from two or more different materials to achieve the optimum pack performance. A common laminate is a biaxially oriented polyester (BOPET) laminated to a low-density polyethylene (LDPE). The BOPET used on the outside provides pack stiffness and gloss and the inner layer of LDPE offers strong seals and hermeticity.

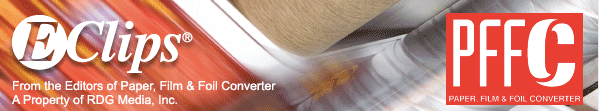

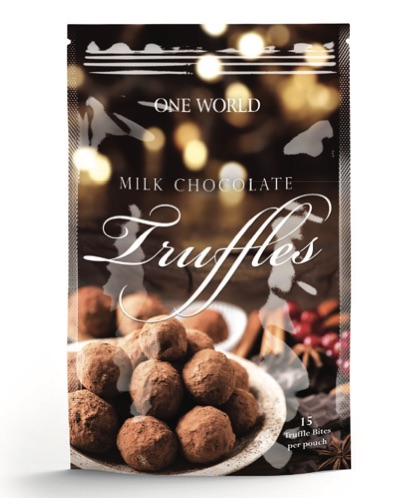

A more sophisticated laminate is used in some pouch applications where barrier to moisture and oxygen is accomplished using an aluminium foil with a reverse printed PET on the outer face and a Cast PP used as the sealant web. Neither of these packs can be recycled back into film, but both give an excellent pack which serves to protect the contents successfully. In both cases it would be extremely difficult to get an effective pack with only one film.

To replace these laminate types, film manufacturers are developing new films with enhanced properties specifically for pouch applications. An example of this is the production of a more thermally stable biaxially oriented polypropylene (BOPP) to replace the BOPET. These products provide lower levels of shrinkage than traditional BOPPs and in some cases offer a non-sealing top skin to prevent jaw stick during packing.

A top web made from BOPP will never have the same temperature resistance as a PET film, therefore Cast PP seal webs need to be designed with a lower seal initiation temperature (SIT) to prevent serious distortion of the BOPP top web. Cast PP films are now available with SITs around 90-degrees Celsius. Options to replace the established PET/LDPE laminate mentioned above, are also now available.

The choice of barrier to replace the aluminium foil is highly dependant on the end application but several PP alternatives already exist. High barrier metallised films or AlOx and SiOx deposition layers can be used although the latter is expensive. Of growing significance is the use of BOPP/EVOH coextrusions where newer products on the market show reduced humidity sensitivity which look likely to open new ground in retort packaging. Providing the content of EVOH/METAL/SiOx/AlOx represents less than 5 percent of the overall pack structure; then full recyclability will be maintained.

Mono material laminates, as proposed above, can be used in a variety of pack formats including lidding, flow wraps, VFFS, sachets and pouches and in several market sectors including confectionery, baked goods, pet food and snacks.

About the Author

Steve Langstaff, CEng (IOM3) in Plastics Engineering with more than 30 years BOPP industry experience, joined UCB (now Innovia Films) in 1990, establishing the foundation of its Pressure Sensitive Label Films business.