The ROl of Automation

- Published: January 26, 2025

Innovation Continues to Drive Increased Manufacturing Productivity

By Tom Kepper, PE, General Manager, Pinnacle Converting Equipment & Services

The long-term demographics of the U.S. labor force are not favoring the domestic manufacturing environment. Additionally, many of the educational opportunities point new entrants into segments of the labor market outside of the factory.

Automation may help ameliorate this trend and its impacts on domestic manufacturing, but there are initial and ongoing cost implications. These changes also require some different methodologies beyond the traditional 18-month payback to invest in new equipment.

Let's first explore the long-term demographics of the U.S. population. The "baby boomers," who were born after World War II, were the largest generation of Americans. Born between 1946 and 1964, there were a total of 76 million births during this time period. The youngest Baby Boomer will turn 65 by 2029, four years from now. Unfortunately, the replacement generation of 5-24 year-olds constitutes a much smaller block of individuals at 43.8 million births. (Source: US Census Bureau).

Workforce participation rates have also been in steady decline since 2000. In March of that year, the workforce participation rate was 67.3 percent. In February of 2020, immediately prior to the Covid-19 shutdown, that rate had dropped to 63.3 percent. After a precipitous, short-term drop in March of that year, the participation rate has mostly recovered, but continues to trend lower and reached 62.6 percent by October of 2024. (See Chart from U.S. Labor Department via Federal Reserve of St. Louis).

Additionally, compare the overall U.S. civilian labor force growth versus the changes in the manufacturing labor force. As far back as 1939, the overall U.S. civilian labor force was 60 million people, and the manufacturing labor force was 9 million (or 15 percent of the overall workforce). U.S. manufacturing reached its peak employment of just under 20 million in the late 1970s.

By October of 2024, the overall U.S. workforce had grown to 168.5 million individuals, while the manufacturing workforce contracted down to 12.9 million (or 7.7 percent of the overall workforce).

Meanwhile, the recently passed Infrastructure Act and Chips Act have estimates that the laws will produce an estimate 871,000 and 277,000 jobs, respectively. (Source: Moodys, Semiconductor Industry Association). It is safe to assume that in geographic locations that are set to benefit from this government intervention, there will be additional competition for individuals currently employed in the manufacturing sector.

So how are the existing industries that are not going to benefit from these interventions going to compete for talent in a smaller skilled labor pool? Via innovation and automation of their own.

A general rule of growth is as follows:

Economic Growth =

Workforce Expansion +

Productivity Gains.

Between 2014 and 2023, manufacturing industrial production growth has averaged 0.8 percent annually, while the average growth in manufacturing employment has only been 0.2 percent (Source BLS, Board of Governors). Based upon those productivity growth numbers and the formula above, if an organization has an expected top line growth rate of 8 percent a year, they would be required to add 7.2 percent more workers.

And where will these workers come from, as we have seen downward trends in the manufacturing labor force? Some companies have developed their own internal training programs, but there is generally no guarantee that the graduates of these programs will remain employed by the company beyond any required commitment period. The alternative is to flip these numbers and increase manufacturing productivity while essentially maintaining the existing labor pool.

Another barometer is with the labor force average hourly earnings rate, which has been increasing by 3.92 per year over the last 10 years. (Source: U.S. Labor Department/Federal Reserve of St. Louis). With wage growth significantly outpacing productivity growth, the long-term profitability of most companies will require increasing manufacturing productivity.

Productivity gains and innovation are hard to come by and often difficult to quantify. One example of a positive breakthrough in manufacturing productivity was the widespread adoption of 3-D CAD/CAM tools in the 1990s. Moving from manual milling machines to CNC machines tied to 3-D modeling tools significantly increased traditional machine shop production and made the new generation of mills interesting to the next generation of operators, many of whom were already comfortable using computers.

However, in the converting space, more specifically with slitter rewinders, the progress of technological innovation often lacked those innovative breakthroughs. With more powerful PLCs and the continued improvements in electronics as a whole, that old paradigm is starting to change. Let's look at several scenarios to examine this statement in greater detail.

Scenario 1: On a typical duplex slitter rewinder with differential rewind shafts used to slit and rewind blown films, two operators are able to run 1,200 lbs. of material per hour. This output is reasonable, but certainly not enough to keep up with the slitting and rewinding requirements of multiple blown film lines. Adding a total of five, non-turreted machines would require 10 operators and result in 6,000 Ibs. of material running every hour or 600 lbs./hr/operator.

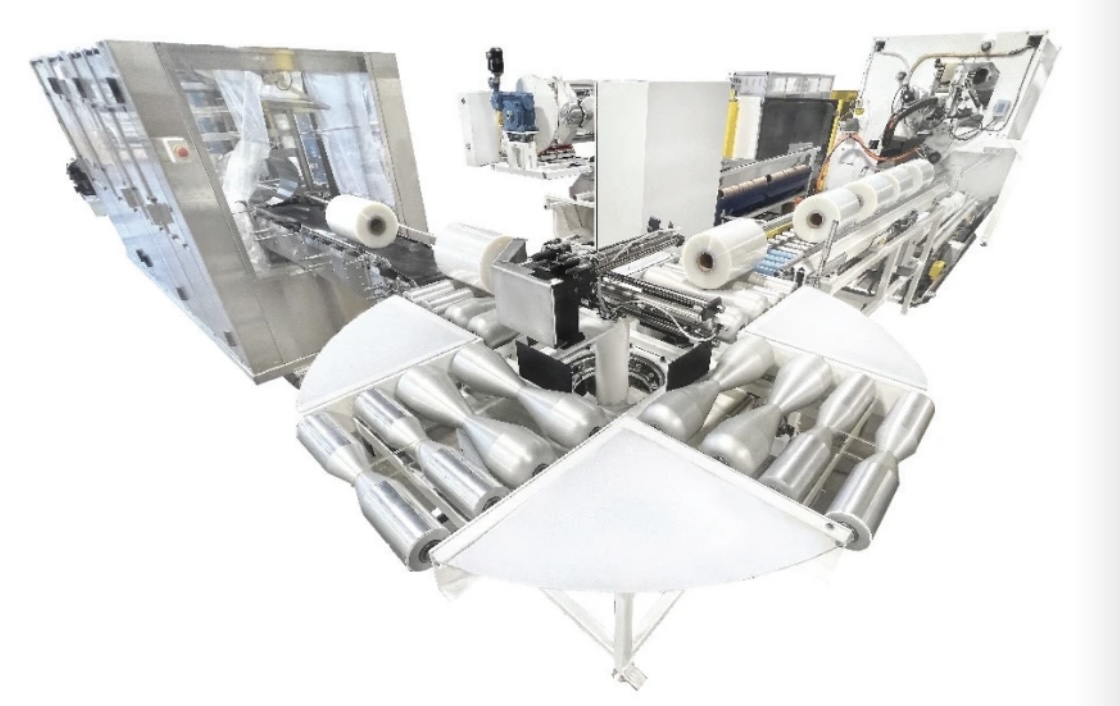

Recent machine developments are enabling significantly more throughput in the course of a typical eight-hour shift. Shaftless unwind stations provide the ability to load rolls without operators handling a heavy shaft, splice stations allow throughput to continue without re-threading the machine, side load blade monitoring systems reduce blade ware, automatic core loading, leading roll edge and end-of-roll tabbing minimize operator engagement, automatic doffing to an exit conveyor and robotic finished roll palletizing eliminate intermediate roll handling requirements.

At the end of a typical eight-hour shift, the increased material output from automation should positively impact the economic growth and profitability of a company actively engaged in slitting and rewinding.

Scenario 2: The fully automated machine described above produces 8,000 lbs. of finished material per hour with four operators. The operators are required to provide master rolls on one of the two unwinds, provide pre-cut cores for the automatic core loader and remove finished pallets after the robotic cell has palletized the finished rolls. Automatic bagging, labeling and other features may further enhance the output of the project.

It is this type of breakthrough performance that will mitigate the reduced manufacturing labor force while providing significantly greater output to provide the corporation with a greater return on investment.

When justifying the additional cost for this type of machine, consider the following factors:

- Increased output to reduce order to fulfilment cycle;

- Reduced labor cost per pound of finished material over a multi-year machine life expectancy;

- Improved safety with automatic core loading, web transfer and doffing;

- Higher residual value of automated machinery;

- Lower cost/unit produced.

While comparing the following hurdles:

- Higher skill level of primary operator;

- Sales levels must be consistent with or exceed machine output levels;

- Higher initial costs;

- Requirement of a skilled maintenance department.

In conclusion, innovation and automation have been the primary drivers of increased manufacturing productivity for multiple decades, not the addition of labor. Similarly, new automation opportunities have the ability to increase the output of slitting rewinding machines. They do so by reducing operator touch points during the slitting process, allowing operators to focus on finished material handling and overall machine throughput, as opposed to manual tasks like core placement and material doffing. The initial costs for these machines may very well be justified by the significant improvement in material output over the multi-decade life expectancy of the machine.

About the Author

Tom Kepper, PE, has been the general manager of Pinnacle Converting Equipment & Services (Charlotte, North Carolina) for the last 10 years. He holds a bachelor's degree in Mechanical Engineering from Vanderbilt University and an MBA from The College of William & Mary. He may be reached at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. or

+1 (704) 376-3855.